Client Alert: Can Works Made with Generative AI be Copyrighted?

In large part, the Guidance attempts to clarify whether AI-generated material is protected by copyright, whether works consisting of both human-authored and AI-generated material may be registered, and what information should be provided to the CO by applicants seeking to register works that include AI-generated material.[i]

This article provides an overview of the Guidance itself and explores various cases that illustrate the CO’s current position on the copyrightability of works made with the assistance of generative AI.

I. Copyright Registration Guidance: Works Containing Material Generated by Artificial Intelligence

A. Requirement for Human Authorship

The Guidance emphasizes the long-standing requirement for human authorship in copyright law. Consequently, the Guidance offers the following key consideration that the CO must undertake in connection with any attempted registration of AI-generated output:

The Guidance, in turn, reiterates that copyright protection is limited to material that is the product of human creativity, and “when an AI technology receives solely a prompt from a human and produces complex written, visual, or musical works in response, the ‘traditional elements of authorship’ are determined and executed by the technology — not the human user.”[iii] However, the Guidance does leave open the possibility that AI-generated works can be registered, provided that a “human had creative control over the work’s expression.”[iv]

As illustrated by a number of decisions discussed in this article, the text prompts that are commonly employed in the current generative AI tools do not appear to involve sufficient human control or creative input in the conception or execution stages of the final output, leading to a general conclusion that any resulting output is not registrable under the current CO policy.

B. Submitting Applications for Works Including AI-Generated Content; Correcting Pending or Registered Applications

For applications currently pending, applicants should contact the CO’s Public Information Office to report any AI-generated material that was not initially disclosed. The CO will then add a note to the record, and the examiner will determine how to proceed.[viii]

For already registered works, applicants should submit a supplementary registration to correct the public record. The supplementary registration should describe the human-authored material and disclaim the AI-generated content, in accordance with the Guidance.[ix]

Applicants should remain mindful of their duty to update and correct their public record with the CO, as the U.S. Copyright Act provides for criminal penalties for anyone who “knowingly makes a false representation of a material fact in the application for copyright registration . . . or in any written statement tied in connection with the application.”[x] In addition, the CO has the authority to cancel any registration where the “material deposited does not constitute copyrightable subject matter” or “the claim is invalid for any other reason.”[xi] Separately, a U.S. court may disregard a registration in an infringement action if it concludes that the applicant knowingly provided the CO with inaccurate information, which further underscores the perils of an inaccurate public record before the CO.[xii]

C. Part 2 of the Guidance

Part 2 of the Guidance, published on January 29, 2025, focuses on the copyrightability of outputs created using generative AI. In part 2, the CO largely reiterates that based on the “functioning of current generally available [AI] technology, sufficient control” over the creative and expressive elements of a resulting work.[xiii] According to the CO, even if the user repeatedly revises the prompts, the analysis remains the same, and the user remains without a sufficient basis for claiming copyright in the output.[xiv]

However, where a user inputs their own copyrightable work and that work is perceptible in the output, the user may have a basis to claim authorship of at least that portion of the output.[xv] Further, a user may select or arrange AI-generated material in a sufficiently creative way such that the resulting work, as a whole, constitutes is an original work of authorship (although not in each of the underlying AI-generated parts).[xvi]

II. Thaler v. Perlmutter, 687 F.Supp.3d 140 (D.D.C. 2023), and Related Decisions

In February of 2022, prior to the issuance of Part 1 of the Guidance, the CO Review Board (“Board”) issued a final determination that an AI-generated work “autonomously created by a computer algorithm running on a machine” could not be registered.[xvii] In that particular decision, the Board considered the applicant’s request for reconsideration of the CO’s refusal to register a two-dimensional artwork, the author of which was identified as a “Creativity Machine” (an AI system capable of generating visual art, according to the applicant). In the relevant application, the applicant further explained that the work had been autonomously created by the Creativity Machine, but that the applicant sought to claim the copyright of the work himself on the basis of the work-for-hire doctrine and the applicant’s alleged ownership of the underlying AI system.The Board determined that human authorship is a prerequisite to copyright protection in the United States and that the work in question could not be registered, as there was no “nexus between the human mind and creative expression” that is the “prerequisite of copyright protection.” Essentially, in the Board’s view, the elements of authorship were not actually conceived and executed by a human, and as a result, the work could not be registered. However, as the applicant did not assert that the work was created with any direct creative contribution from a human author/user, the Board did not determine under what circumstances human involvement in the creation of AI-generated works would meet the statutory criteria for copyright protection.

The Board’s decision was later upheld by the U.S. District Court for the District of Columbia, which rejected the applicant’s contention that the AI system itself should be acknowledged as the author, with any copyrights vesting in the AI’s owner. The court further held that the CO did not act arbitrarily or capriciously in denying the application, reiterating the requirement that copyright law requires human authorship and that copyright protection does not extend to works “generated by new forms of technology operating absent any guiding human hand, as plaintiff urges here.”[xviii] The court further emphasized that the Copyright Act and the Constitution have always been interpreted to require human authorship, such that works generated autonomously by machines without human involvement, as claimed by the applicant in the present case, are not eligible for copyright protection.

Similar to the Board’s decision, the District Court left unanswered the question of how much human input or involvement is necessary to qualify the user of an AI system as an “author” of a generated work, and the scope of the copyright protection available over the resultant image(s). This case is presently on appeal before the D.C. Circuit, and additional clarity may emerge from the appellate court’s decisions.

III. Zarya of the Dawn

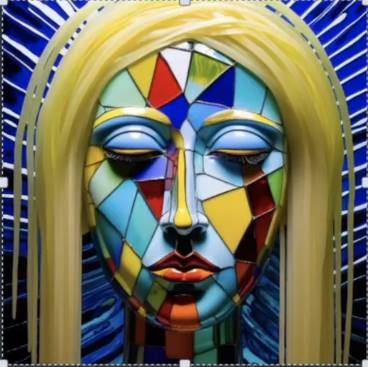

A number of other decisions by the CO and the Board have weighed in on the copyright registrability of AI-generated works, including decisions where, unlike the Thaler matter discussed above (autonomously generated content), certain human involvement was alleged (in the form of AI prompts and other input by a human user).In the case of Zarya of the Dawn, a few weeks before issuance of the Guidance, the CO had initially granted a copyright registration for a comic book created by Kristina Kashtanova using the AI tool Midjourney. The initial application did not disclose that AI was used to create any part of the comic book. Upon discovering that the images in the book were generated by AI, the CO reevaluated the registration, concluding that while the text and the selection, coordination, and arrangement of the text and images were protected by copyright, the individual AI-generated images were not.[xix] A representative text prompt by Ms. Kashtanova, and the resulting final image generated by Midjourney, are reproduced below.

The process described by Ms. Kashtanova involved providing text prompts to the AI, which then generated images. The CO found that this process did not involve sufficient human control or creative input to qualify the resulting images for copyright protection, concluding that the images generated by Midjourney in response to Ms. Kashtanova’s text prompts were not the product of human authorship.[xx] The CO decision, in particular, appears to be premised on the fact that a user of Midjourney cannot predict what will be created ahead of time, and therefore lacks the control of the creative process, “no matter how similar [the resulting images are] to the artistic vision” of the user.[xxi]

Consequently, the CO canceled the original registration, and a new registration was issued, excluding the AI-generated content.

IV. Théâtre D'opéra Spatial

Jason M. Allen's artwork, Théâtre D'opéra Spatial, was initially created using the AI tool Midjourney, and further adjusted by Mr. Allen in Adobe Photoshop. The Midjourney image and the final work are reproduced below.

The CO denied Mr. Allen’s registration for the final work because the work contained more than a de minimis amount of AI-generated material. Mr. Allen argued that his creative input in providing text prompts and making adjustments should qualify him as the author. However, the Board affirmed the denial, stating that the traditional elements of authorship were determined and executed by the AI, not by Mr. Allen.[xxii]

Similar to the CO decision in Zarya of the Dawn, the Board concluded that Allen's prompts and iterative process (totaling at least 624 prompts) did not amount to human authorship. The refusal to register the work was based on the lack of human creative control over the AI-generated content, and the applicant’s refusal to disclaim the AI content from the registration.

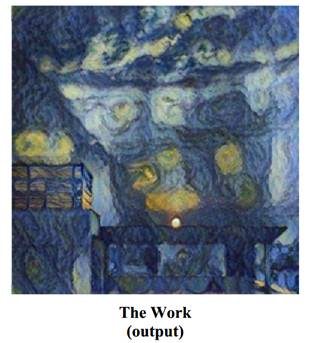

V. SURYAST

Ankit Sahni's 2-D artwork, titled SURYAST, was created using the AI tool RAGHAV, which applies artistic styles to pre-existing photographs submitted by the user. In the relevant part, Mr. Sahni provided 2 images to RAGHAV—an original photograph (as a base image), and a second image as a style input, for which Mr. Sahni selected “The Starry Night” by Vincent van Gogh. As part of additional user prompts within RAGHAV, Mr. Sahni further selected a variable value for the amount of style transfer from the style image onto the base image. The choice of the base image, the style image, and the variable transfer values have an influence on the final generated output by RAGHAV.

Mr. Sahni’s registration was initially denied by the CO, and the Board affirmed the decision, again on the basis that the expressive elements of the final work were determined by the AI tool itself, not by Mr. Sahni.[xxiii]

The Board found that Sahni's inputs within the RAGHAV tool did not constitute sufficient human authorship. According to the Board, “RAGHAV’s interpretation of Mr. Sahni’s photograph in the style of another painting is a function of how the model works and the images on which it was trained—not specific contributions or instructions received from Mr. Sahni.”[xxiv] As such, in the Board’s view, the AI tool RAGHAV was responsible for the creative elements of the final image.

VI. Registration of an AI-Generated Visual Collage

On January 30, 2025 — one day after publishing Part 2 of the Guidance — the CO allowed copyright registration of a visual collage, comprising an initial image generated by the Invoke AI tool, which was subsequently revised by the applicant by focusing on the specific regions of the image and generating new AI elements in each area — 35 specific areas in total — with a series of additional prompts. This process is generally known as “inpainting.” In this instance, according to the CO, the resulting collage as a whole contained a sufficient amount of human original authorship in the selection, arrangement, and coordination of the AI-generated material such that the entire image (but not the specific elements) could be copyrighted. Importantly, the applicant appropriately disclaimed the underlying images generated by AI in its application.

VII. Conclusion

The CO's current position on the copyrightability of works made with the assistance of generative AI, as reflected in the Guidance and the decisions discussed in this article, largely suggests that works generated by AI, without sufficient human creative input and control, do not qualify for copyright protection. The current CO position has created a void of ownership in connection with certain AI-generated works, and it appears that general text and other user prompts in tools like Midjourney and RAGHAV are insufficient to enable a user to claim authorship in the resulting output. As noted in the Guidance, this is a case-by-case inquiry, and the answer in each case will depend on the specific circumstances, particularly how the AI tool operates, and how it was used to create the final work. Following the successful registration of the visual collage generated by the Invoke AI tool, there is at least some instructive guidance for applicants who may be interested in seeking registration of works based on the selection and arrangement of certain AI-generated material.In the absence of future court intervention or legislation that overturns or addresses nuances in the use of AI tools to create works, human authors, coders, and other creators remain indispensable to the protection of works created using AI, as only their creative expression is protectable under the U.S. copyright law. For those entities using generative AI technology in their businesses, customary representations and warranties regarding IP ownership may not be appropriate with respect to AI-generated deliverables, and care should be taken to appropriately tailor any service, sale, license, or corporate transaction agreements in light of the fact that copyright protection may not be available for certain AI-generated works. For substantially the same reasons, in order to secure and maintain rights to AI-generated works, businesses should seek protections under areas of law other than copyright, such as by protecting outputs as trade secrets or otherwise seeking contractual protections that impose confidentiality restrictions on disclosure.

Notably, the CO has launched an initiative examining copyright law and policy issues raised by AI and will be issuing additional reports intended to further address, among other issues, the use of copyrighted materials in AI training. This remains a rapidly developing area of the law that Whiteford will continue to closely monitor.

The information contained here is not intended to provide legal advice or opinion and should not be acted upon without consulting an attorney. Counsel should not be selected based on advertising materials, and we recommend that you conduct further investigation when seeking legal representation.