Associations, Nonprofits and Political Organizations Report - Summer 2023

Whiteford is Founding Donor of ASAE Foundation's John Graham DEI Fund

By: Jefferson C. Glassie, FASAEThe Whiteford Associations, Nonprofits and Political Organizations practice group is continuing its five-year commitment as a Founding Donor of the ASAE Educational Foundation’s John Graham Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion Fund. The Fund is a restricted fund administered by the ASAE Foundation to support the development of research, resources, tools, and programs to help associations in their DEI journey. The ASAE Foundation recently announced it would award 20 scholarships to deserving applicants pursuing professional and personal development through ASAE’s ReadyMe Program. The ReadyMe program formally launched last August during ASAE’s 2022 Annual Meeting & Exposition. The program provides a combination of virtual and in-person learning experiences that will build resilient and adaptable leaders by unlocking vital social skills and the career management acumen they need for advancement and success in the association industry. Whiteford is proud of its longstanding commitment to supporting ASAE and the ASAE Foundation, having been a major donor of the ASAE Innovation Grants program for the five years prior to supporting the John Graham DEI Fund.

Best Practices to Maintain an Enforceable Code of Conduct

By: Mark C. Franco, ICE-CCPOriginally published by ASAE here

A code of conduct outlines an organization’s mission, values, and principles, and links them with standards of professional conduct. Here’s an overview of key issues to consider when implementing an enforceable code of conduct for your association.

Last year, ASAE added diversity, equity, and inclusion components to its Standards of Conduct. ASAE promotes these Standards of Conduct because more than 287 million people around the globe look to associations for their vision, values, and effectiveness.

However, apart from individuals who have earned a CAE, the ASAE Standards of Conduct remain primarily aspirational. While the conduct is desired, it is not required for membership. But ethical conduct is mandatory and enforceable for those with a CAE credential since a code of conduct is critical to the credential and required under third-party accreditation standards.

Many associations adopt an aspirational code of conduct or ethics because they allow for more flexibility and freedom in their administration. However, other associations find enforceable codes of conduct are necessary to protect the public and the reputation of the profession, particularly in industries like healthcare or finance where professional conduct can affect public safety and well-being.

While necessary, organizations that adopt an enforceable code must understand and pay attention to very specific legal requirements. Here’s a closer look at what those entail.

Enforceable Codes 101

At their foundation, enforceable professional codes of conduct or ethics must be fair and reasonable. They should relate to the organization’s mission and should be no more stringent than necessary.

Any enforceable code must maintain a balance between specificity, to provide reasonable notice of what may be prohibited conduct, and generality, to allow for flexibility. An enforceable code should not unreasonably restrict or restrain trade, unfairly diminish a professional’s ability to practice or engage in business, or otherwise run afoul of or violate antitrust laws.

Associations can generally adopt enforceable codes of conduct or practice that prohibit practices, policies, and conduct that are commonly considered to be illegal, largely improper, or unacceptable.

Enforceable codes can usually prohibit unprofessional conduct, such as practicing under the influence of alcohol or drugs. They can also prohibit criminal behavior and other general crimes of moral depravity. Most importantly, they can generally prohibit conduct that would be considered violations of professional practice.

However, enforceable codes cannot be used to “blackball,” inappropriately exclude, or subject members to unreasonable restrictions disguised as “unethical” behavior or professional “misconduct.”

To be fair and reasonable, enforceable codes of conduct or ethics must be both substantively and procedurally fair, providing “fundamental fairness” to those that are subject to it. An enforceable code is substantively fair if it is not developed on or applied on an arbitrary basis and is “rationally related” to a “legitimate concern” of the association. For example, it likely would not be substantively fair for an association’s enforceable code to make owning a red car a violation.

Handling a Violation

In the event of an alleged violation of an enforceable code of conduct or ethics, procedural fairness requires that an association provide advance notice and an opportunity for the individual to explain the situation. Any findings of a violation must be based on substantial evidence.

An association must also provide a reasonable opportunity to appeal any adverse decision to a separate decision-maker who can handle any due process (fairness) challenges or concerns. This includes the ability to determine whether the association followed its own rules in enforcing the code of conduct or ethics. But fairness does not require rigid adherence to procedures so long as the results were generally consistent with fairness requirements.

When adopting an enforceable code of conduct or ethics, legal considerations require that written notice must be provided to potential violators that clearly presents any alleged violation and identifies the specific conduct that may be a violation. Determinations of violations must be made by impartial decision-makers such as peers in the profession. An opportunity for appeal must be allowed.

It is generally good practice that regardless of whether aspirational or enforceable, an association’s code of conduct or ethics should ensure that it is administered fairly and equally to all those subject to it.

Data Breaches and Your Privacy/Cybersecurity Program

By: Bruce F. Martino, CIPP/G, CIPMData breaches have become a commonplace occurrence. Nearly every business, including nonprofits, collects, stores and uses personal information (PI) that is valuable to bad actors. All organizations store and process PI about their employees. Many nonprofit organizations store and process PI about their donors and volunteers. Bad actors can cause financial harm to the individuals whose PI is stolen.

California was the first state to try to protect affected individuals from this harm. It enacted a data breach notification law[i] nearly 20 years ago. The rationale behind the law is that individuals who have notice of a breach can take steps to protect themselves from identity theft and financial harm. All 50 states, the District of Columbia (District), Guam, Puerto Rico and the Virgin Islands now have a data breach notification law. These laws require organizations which collect, use and store PI to notify consumers if their PI is breached.

This article will briefly describe the District, Maryland and Virginia data breach notification laws. It will then discuss how an organization can mitigate the risk of a data breach by implementing a privacy and cybersecurity program and related processes and controls.

A. Data Breach Notice Laws

There are 50+ data breach notice laws in the United States[ii]. There are similarities among the current District, Maryland and Virginia laws. Breach is defined as the unauthorized acquisition of computerized data that compromises the security, confidentiality or integrity of PI.[iii] The cause of the breach is irrelevant. It can result from criminal activity or employee error, for example, sending PI to the wrong individual. Encrypted PI does not trigger data breach notification even if a bad actor infiltrates a system in which PI is stored.

It is important to remember that nonprofit organizations are not exempt from reporting a data breach under the current District, Maryland and Virginia laws.

The District’s data breach notification law[iv] went into effect on June 8, 2020. PI is defined as the first name or initial and last name plus social security number, passport number, driver’s license number, financial account number with access code or password, medical information, genetic information or biometric information. This is not an exhaustive list. Organizations which suffer a breach must notify affected individuals as soon as possible and without unreasonable delay. Notice must also be sent to the District’s Attorney General (AG) and consumer reporting agencies under certain circumstances. Notice is not required if the organization determines it is unlikely the individuals will be harmed. That determination must be after investigation and consultation with the AG.

Maryland’s data breach notification law[v] became effective on January 1, 2008, and has many similarities to that of the District. The definition of PI is similarly broad. Notice does not need to be given in the case of a breach of unencrypted PI if the organization reasonably determines the PI will be not be misused, for example, for identity theft. Notice must also be sent to the Maryland Attorney General under certain circumstances.

Virginia’s data breach notification law[vi] was effective as of July 1, 2008. It is not as consumer friendly, at least with regard the definition of PI, as the District and Maryland laws. PI is limited to first name or first initial and last name in combination with social security number, driver's license number or state identification card number, financial account number with a required access code, passport number or military identification number. For example, notice is not required under the Virginia law if a bad actor acquires a consumer’s health information.[vii]

An organization must notify affected individuals of a breach of unencrypted PI without unreasonable delay if the organization reasonably believes the affected individuals have been or will be the victim of identity theft or fraud. The Virginia Attorney General and consumer reporting agencies must also be notified under circumstances described in the law.

There are differences among the three laws. First, Virginia’s definition of PI is not as broad as those set out in the District and Maryland laws. Next, notice in Maryland must be given as soon as possible but not later than 45 days after the organization discovers or is notified of a breach. The timeframes in the District and Virginia are without unreasonable delay. Finally, the District law does not apply to its government agencies. Maryland and Virginia do not exempt their state government agencies.

B. Your Privacy and Cybersecurity Program, Processes and Controls to Implement

Data breaches are costly. IBM reported in 2022 that the average cost of a data breach was $4.35 million dollars[viii]. The costs include fees charged by cybersecurity forensics consultants, outside attorneys and public relations firms. There can also be costs relating to data restoration, system downtime, modifying systems to eliminate the cause of the breach and notifying affected individuals. In the case of ransomware, some breach victims choose to pay the demanded ransom. Some organizations do not have cybersecurity insurance. Those that do have high deductibles. Building an effective program, which uses reasonable and appropriate security measures, lessens the chance of a data breach.

There are six steps a business should take to implement a privacy and cybersecurity program. They are:

- Data Mapping/Data Classification. Many businesses do not know the systems and databases in which the PI they collect is processed and stored. In addition, many businesses use third parties to process and store PI. Data mapping is a process by which a business locates its PI and tracks it to each system used to process and store the PI. Do not forget PI stored in hard copy.

- Risk Assessment. A business should then assess the risks around processing and storing its PI. Measure current practices against a set of industry recognized data handling practices. Remediate the gaps.

- Policy, Process and Procedures. Written privacy and security policies, processes and procedures related to handling and storing information should be adopted. Regulators will ask for these if the business is investigated.

- Incident Response Plan (IRP). Every organization needs an IRP. The IRP sets out procedures that will be followed when the business has a known or suspected security incident. Test the IRP periodically via a table top exercise.

- Training. Many security incidents occur because well-meaning people are not careful or knowledgeable. It is crucial to train staff and volunteers on secure data handling practices. For example, train staff and volunteers on what to look for in spotting a phishing email. Personnel who have been trained are far less likely to open a phishing email.

- Audit. Audit your program and address the gaps. Strive for constant improvement.

- All confidential information, including PI, should be encrypted at rest and in transit. Bad actors cannot use encrypted information.

- Require users to use complex passwords. A password should be at least 8 characters that include upper and lowercase letters, numbers and symbols. Establish a requirement to change passwords at least every 90 days.

- Make multi-factor authentication mandatory. A second log-in credential decreases the ability of bad actors to infiltrate an employee’s account.

- Keep all software updated with the latest patches and security configurations.

- Consider buying cyber insurance.

- Train employees and volunteers to be wary of working in public spaces using public WiFi and hot spots. Be sure each is using a VPN.

C. Conclusion

There is an old adage. An ounce of prevention is worth a pound of cure. No amount of effort will make an organization completely breach proof. However, a well thought out, risk-based privacy and cybersecurity program will make it difficult for bad actors to gain access to an organization’s data.

[i] Cal Civil Code § 1798.29.

[ii] There is no overriding federal law on data breach notification.

[iii] Code of the District of Columbia § 28-3851 (1)(A), Md. Code Comm. Law § 14-3504 (a)(1) and Va. Code § 18.2-186.6.

[iv] Code of the District of Columbia § 28-3851, et seq.

[v] Md. Code Ann Comm Law § 14-3501, et seq.

[vi] Va. Code § 18.2-186.6.

[vii] The Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act, also known as HIPAA, requires notice under certain circumstances.

[viii] IBM, Costs of a Data Breach Report 2022.

Volunteer Management

By: Eileen Morgan Johnson, CAEVolunteers are an important part of the nonprofit community. Almost all organizations started with an idea and the hard work of one or two people. Many organizations operate solely with volunteers. Others use volunteers to expand their programming efforts. The vast majority of nonprofit board members are volunteers. Savvy managers realize volunteers can pose risks to an organization if they are not well managed in the areas of recruitment, training and supervision.

Recruitment

A written volunteer application will help an organization to obtain information on an applicant so that the best use can be made of the applicant’s experience and talents.

In addition to the applicant’s name and basic contact information, a volunteer application should collect information on the applicant’s education, work experience, previous volunteer experience, and support for your organization’s mission.

Screening Volunteers

Of course, not every volunteer is right for every organization.

Organizations should require background checks of any volunteers who will be working with children, the elderly or the disabled, handling money or driving a vehicle. They can check the applicant’s criminal, credit, motor vehicle and child protective services records to the extent such reviews are permitted by state law. Background checks can now be done quickly and inexpensively thanks to the Internet.

A volunteer application should include a notice that the organization will conduct a background check, the type of background check to be conducted, and a place for the applicant to authorize it. If the volunteer application is on-line, it will need a separate form authorizing the background check that applicants can download, sign and deliver to the organization.

Special care should be taken with volunteers who drive vehicles as part of their duties. They should be asked to provide a copy of their driving record. The organization’s management should review the driving record and ask if this is a safe person to be driving on behalf of the organization. The driving records of any volunteers who drive for an organization should be reviewed annually. The organization should also check with its insurance carrier to see which insurance policy, the organization’s or the volunteer’s, will be primary in the event of an accident and the volunteers should be given this information. As an additional step, volunteer drivers can be given an accident report form to carry in their vehicles and complete if an accident should occur.

If volunteers need any skill certifications or licenses to perform their volunteer duties, a copy of their certification should be kept in the organization’s file. Examples of skill certifications are first aid, CPR and lifesaving. Licenses are usually required for professionals such as nurses, doctors and veterinarians. Someone should regularly check to make sure all volunteer certifications are current.

Orientation

All volunteers should receive orientation. The orientation program should be customized to fit the needs of the volunteers. At a minimum it should include a brief history of the organization, a review of the mission and current strategic goals, and a review of the volunteer handbook. The orientation should also provide information to each volunteer about what they will be doing for the organization and how their role fits into the organizational structure and meeting the organization’s mission.

Volunteer Handbook

A volunteer handbook can help to quickly integrate volunteers into an organization. It can also help to reduce or eliminate potential legal problems. The volunteer handbook should clearly communicate to an organization’s volunteers what they can expect from the organization and what the organization expects from them. Every volunteer should receive a copy of the handbook and sign a receipt acknowledging that they received a copy and have read (or will read) it. The volunteer handbook may also be posted on the organization’s website for easy access and updating. If the handbook is posted on-line, the acknowledgment the volunteers sign should indicate that the most current version of the handbook will be on-line.

A good volunteer handbook includes:

- Basic information about the organization – its history, mission, values and strategic goals;

- Policies that impact volunteers;

- Procedures that volunteers should follow;

- Information on how volunteers and staff are integrated in the organization;

- Explanation of any terms, program names or acronyms used by the organization;

- Volunteer benefits (if applicable);

- Samples of forms; and

- Volunteer recognition programs.

Policies and Procedures

Policies to include in a volunteer handbook are: nondiscrimination, sexual harassment, conflicts of interest, confidentiality, code of conduct, copyright and trademark use, e-mail use, privacy, dress code, evaluations, travel, use of property, publicity and political activity. Each policy should be reviewed by an attorney to ensure that it complies with current state and federal laws.

Examples of procedures to include in a volunteer handbook are scheduling, purchasing, petty cash, expense reimbursement, and access to the organization’s premises after hours. Having clear and detailed procedures on purchasing, petty cash and expense reimbursement can help to reduce the likelihood of any impropriety arising out of a volunteer’s handling of money or purchases.

Training

New volunteer should receive instructions on their particular duties and training on any equipment to be used. They should be told who can answer their questions. A volunteer mentor or a staff member should be designated as the person to provide guidance as the new volunteer becomes familiar with the organization and the volunteer’s duties.

All volunteers should receive training. This gives the organization an opportunity to share new information with its volunteers and review information previously presented. It is also an opportunity to correct any practices or bad habits that may have arisen that are not in compliance with the organization’s policies and procedures.

Some organizations require specific training (such as youth protection) that should be repeated after the passage of time. Other organizations keep track of who has completed a training program and the date of completion and will not allow volunteers to participate if their training has “expired.”

An organization’s training program may vary depending on the material it has to convey to its volunteers and their demographics. It is important to measure the effectiveness of the training programs and make changes as needed to keep them fresh and responsive to current volunteer needs.

Expectations

No matter what their level in the organization, volunteers cannot be successful unless they have been provided the information and the opportunities they need to succeed. A good orientation and training program, volunteer handbook and clear policies and procedures will help to set the framework of the organization’s expectations, but the volunteer also needs to know how all of that applies to his or her specific volunteer duties. Volunteer “job descriptions” are helpful in describing what the volunteer should be doing and in setting boundaries for what might be beyond the scope of the volunteer’s authority. Setting spending limits for the organizations funds or indicating who is authorized to speak to the press are examples of setting boundaries. Rather than suffer in silence, if a volunteer has gone beyond what was expected (in a negative sense), someone in authority needs to politely speak with the volunteer and reinforce the volunteer’s role in the organization and the boundaries for that role.

Supervision

Volunteers should be adequately supervised. The supervisor can be a staff member or an experienced volunteer. The supervisor should treat any volunteer failures or misconduct appropriately including documenting any complaints and any action plans to improve performance.

Sometimes an organization has a problem volunteer whose service needs to be terminated. The reason for the termination should be clearly stated to the volunteer and documented. While it is always difficult to fire someone, sometimes it is in the organization’s best interest to terminate a volunteer. Someone who is verbally abusive to staff, volunteers, members or clients is doing more harm than good. A volunteer who exceeds the given spending authority or is quick to place a phone call to the media is a serious problem. Termination is a drastic step and efforts can be made within reason to improve performance but sometimes terminating a volunteer is the only thing an organization can do to protect the organization.

Volunteer Recognition

Although volunteer recognition programs are often focused on recognizing and rewarding devoted volunteers, they have other uses as well. Recognition – even if it is as simple as a service pin or an annual luncheon – can help to motivate and retain volunteers who might otherwise lose interest in their volunteer work. Recognition can also be used to help guide the behavior and improve the performance of volunteers who are not meeting the organization’s expectations. By recognizing outstanding volunteers, the organization is affirming for the other volunteers what it takes to be a successful volunteer. Events that recognize outstanding volunteers also open the door for conversations with other volunteers as to why they were not selected and what they can do to improve their performance.

Volunteer Protection

Federal and most state laws (including the District of Columbia) give special protections to volunteers. The federal Volunteer Protection Act of 1997 protects volunteers from personal liability for harm they cause unintentionally while serving as volunteers. This protection only applies to the volunteers and it only protects them for claims by injured parties. It does not protect a volunteer for claims by the nonprofit organization nor does it protect the organization from liability for failure to adequately train or supervise the volunteer.

To qualify for the federal protection, a volunteer must meet four conditions: 1) the volunteer must have been acting within the scope of his or her responsibilities as a volunteer at the time of the act or omission; 2) if a license is required for the volunteer’s activities, the volunteer must have been properly licensed; 3) the volunteer must not have been acting with willful or criminal misconduct, gross negligence, reckless misconduct, or a conscious, flagrant indifference to the rights or safety of the individual harmed; and 4) the harm may not have been caused by the volunteer operating a motor vehicle, vessel, aircraft, or other vehicle for which the state requires the operator to have a license or the owner to maintain insurance.

Most state volunteer protection statutes are modeled on the federal law. Some states have separate statutes that provide protection from liability for medical personnel (doctors, nurses, EMTs, etc.) performing volunteer emergency service at the scene of an accident or natural disaster. A few have similar protection for veterinarians providing emergency veterinary services.

Insurance

Organizations should regularly review with their insurance broker any changes in their programs and their use of volunteers. Directors and officers liability policies (known as D&O policies) cover the actions of volunteers serving as board members and officers but rarely cover other volunteers. Most nonprofit association liability policies cover volunteers. Organizations should have both a D&O policy and a general liability policy. Additional insurance such as automobile or multimedia coverage may also be advisable. Organizations should make sure all of their policies cover their volunteers.

Conclusion

Volunteers are an important asset of any organization. The volunteers and the organization will all benefit from an appropriate recruitment, training and management program. It takes time and organizational resources to have a strong volunteer program but the rewards are worth the effort.

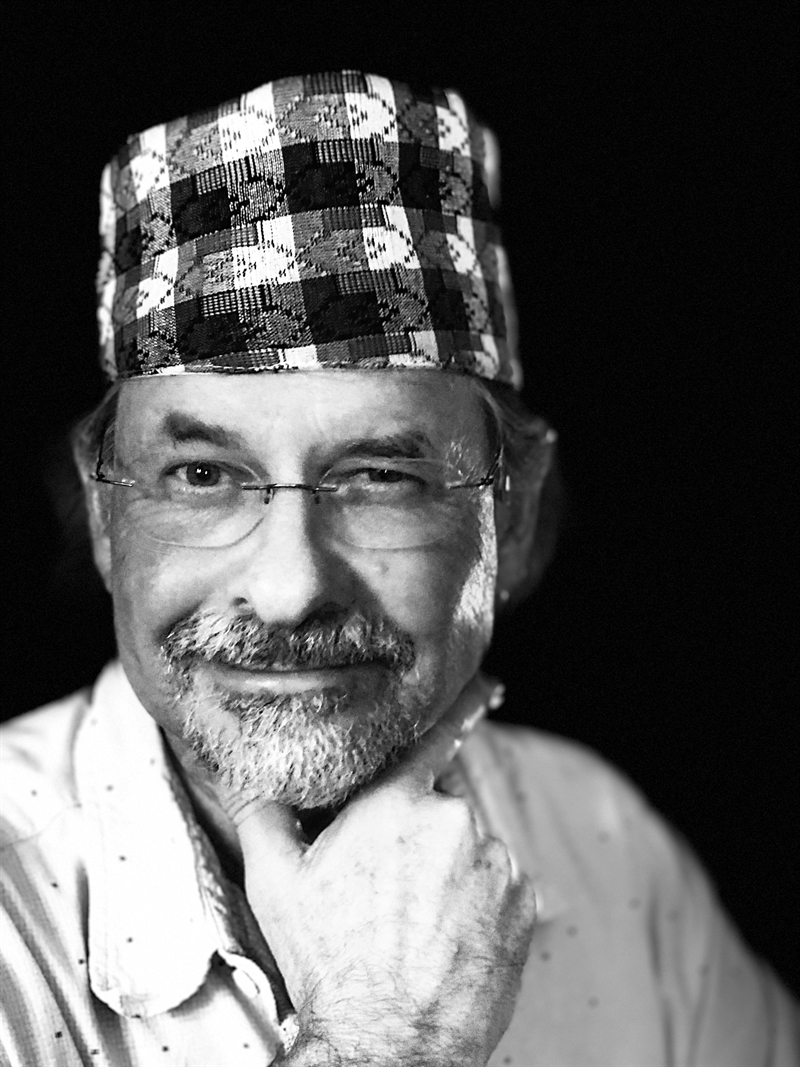

Attorney Spotlight - Steven Benson

Steve Benson has been working with nonprofit associations and tax exempt organizations for nearly 40 years. He began his practice of law on active duty as a Navy JAG attorney and transitioned to the world of nonprofit law when he left military law practice. Steve serves as General Counsel to a number of nonprofit organizations with an emphasis on professional membership associations. Steve regularly counsels his clients on all aspects of Board duties and governance.

When not working, Steve enjoys hiking, biking, golfing, and other outdoor activities. Steve also enjoys traveling with his wife to visit their three boys on the West Coast in Los Angeles and Las Vegas.

Announcements